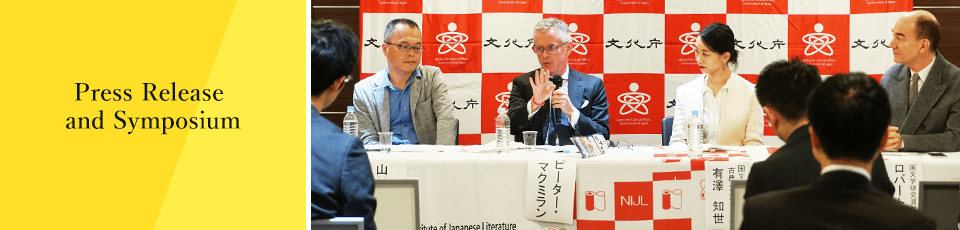

NIJL Arts Initiative Press Release and Symposium

(2017.10.18)

Greetings from the sponsor (Yukinori Takada, head of the National Archives of Modern Architecture, Agency for Cultural Affairs, Policy Planning and Coordination Division of the Agency for Cultural Affairs)

Takada:

Good morning everyone. I would like to say a few words on behalf of the Agency for Cultural Affairs.

I would like to express my gratitude towards the press, related officials and speakers holding talk shows afterwards for coming today. The Agency for Cultural Affairs is currently promoting cultural programs in preparations for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics. It is written in the Olympic Charter that not only as a sports festival, but also variety of programs that fuse culture and education will be carried out. Especially in recent years, various events were carried out through cultural programs at the London Olympics and Paralympics. This was not only for the promotion of culture and arts, but also for the promotion of economic and social aspects such as the increase in the ranking of London and England, increase in tourism and an increase in different creative activities due to culture and arts programs. International exchange also became active, becoming a stimulation for various artists resulting in creative activities flourishing.

Considering these advantages, the Agency for Cultural Affairs is cooperating with different kinds of institutions carrying out projects to expand the range of our partnership. This joint project with the National Institute of Japanese Literature is not just a promotion of arts and culture. We aim to carry out projects and events which will promote expansion in many different areas such as education, academic fields and international exchange.

A detailed description of the projects will be provided by related officials afterwards, so I would just like to say that we, as the Agency for Cultural Affairs, consider these projects as extremely important projects and we look forward for your support. Thank you very much for your time.

Overview (Koyama, Head of Planning and Public Relations Office, National Institute of Japanese Literature)

Koyama:

My name is Junko Koyama and I am the Head of Planning and Public Relations Office at the National Institute of Japanese Literature. I would like to give an explanation about our project. This new project was commissioned to the National Institute of Japanese Literature by the Agency for Cultural Affairs and is called the NIJL Arts Initiative: Innovation through the Legacy of Japanese Literature. This is a part of the initiatives taken by the Agency for Cultural Affairs for sharing Japanese culture overseas with the aim of delving into classic literature and connecting it with society and the creation of new art.

Since its establishment, the National Institute of Japanese Literature has investigated classic literature for approximately half a century, scanned images and made them available to the public. We have accumulated a massive amount of literary materials. These materials are important and vital to Japanese literature and culture research. This new project aims to not only use this scale of literary resources for research, but to also expand its range of utilization.

The NIJL Arts Initiative consists of three sections. The first section is the Artists in Residence. This involves inviting artists who create works of art in various fields, and to create new art works based on the senses and knowledge gained by coming in touch with classic literature. Participating artists include the novelist who has won many awards including the Akutagawa Prize, Hiromi Kawakami. Ms. Kawakami released a modern translation of Tales of Ise in 2016. Unfortunately, as stated earlier, Ms. Kawakami is absent today due to unavoidable circumstances. Another artist is playwright, director and actor Keishi Nagatsuka who is active in a variety of different fields. Animation artist Koji Yamamura has also been involved in the project. He is highly regarded for his work inside and outside Japan.

The second section is the Translator in Residence. This part involves inviting a translator who translates Japanese literature into foreign languages and the National Institute of Japanese Literature providing support in the translation of classic literary works that have not been introduced overseas. We have invited Peter MacMillan as the Translator in Residence. MacMillan provided a new translation for Tales of Ise last year which was published by Penguin Classics and released One Hundred Poets, One Poem Each in 2017.

In order to carry out this work, an expert navigator is necessary. This is the third section of this project, the Classics Interpreter. We have employed young and talented researchers as specially appointed teachers to act as navigators of classic literary knowledge in areas such as selection and interpretation of works as well as access to expert information. That has been an extremely simple description of the works going on at the NIJL Arts Initiative.

Participant introduction

Koyama:

Continuing, I will introduce the artists, translator and classics interpreter attending today. Please take a seat as I call your name.

Playwright, director and actor, Keishi Nagatsuka.

Animation artist, Koji Yamamura.

Translator, Peter MacMillan.

Special appointed teacher of the National Institute of Japanese Literature and classics interpreter, Tomoyo Arisawa.

Director of the National Institute of Japanese Literature and representative sponsor, Robert Campbell.

The symposium will start from now. I will hand over the emcee duties to Mr. Campbell.

Symposium

Campbell:

Thank you very much. Welcome to the NIJL Arts Initiative press release. My name is Robert Campbell and I was appointed as Director of the National Institute of Japanese Literature from April this year. Since we are gathered here together, I would like to spend about 30 to 35 minutes talking about the goals of this Initiative and sharing the ideas of each artist and translator. As Professor Koyama mentioned earlier, the National Institute of Japanese Literature has many classical literature, in other words, actual Japanese books that were hand written or printed before the Meiji Period (1868). We have over 20,000 original books plus a database server with a much larger amount of information on it. Over the past half century, we have been to various places including libraries, private homes, shrines and temples in 70 locations around the world and 1,000 locations in Japan and investigated each individual piece of classic literature. From all the titles we have investigated, we selected around three-fifths of all the titles and scanned images of all of their pages. We have come up with different ways to make this collection of classic literature images available publicly and freely on online. Using these as materials, our research institution makes and accept proposals to university professors nationwide on joint research.

In addition, NIJL has been promoting a ten-year large scale research project ("Project to Build an International Collaborative Research Network for Pre-modern Japanese Texts (NIJL-NW project) http://www.nijl.ac.jp/pages/cijproject/). There are plans to create an image database of over 300,000 classic literature titles significantly exceeding 1 million books by 2023. This currently underway construction will not only be limited to literature, but also in the fields of industry, natural sciences and life sciences. This large project unprecedented in the world is expected to change our understanding of Japanese literature, history and culture as well as how we utilize this information. While making it an international collaboration, we believe it is also necessary to clarify what we are creating and what will be created including new culture, objects, ideas and expressions.

We have also carried out different kinds of contests and joint researches with researchers in varying fields. For example, we selected individual recipes from cook books published during the Edo Period 200 and 300 years ago, translated them into modern Japanese and held an Edo Cuisine Fair with food developed for modern times in collaboration with chefs at the Mitsukoshi Main Location in Nihonbashi from late September to early October of this year. The aim of this NIJL Arts Initiative is to tirelessly use the stories, dramas and texts located in NIJL to create new objects and expressions and to translate them into various languages in order to share the abundance of Japanese literature and culture with the world. Three guests have come to talk with us today. Including Hiromi Kawakami, who could not be here today, these people became our Artists in Residence (AIR) each handling different types of genres and materials. AIR is a system that is common in Western countries. Artists are invited to certain institutions to take on the task of creation while coming into contact with resources for a set period of time. This Initiative aims to create a place to create works of art and translate classics into other languages like a real laboratory, while utilizing our network of researchers in Japan and overseas in addition to the collection of classic literature we have accumulated over a long period of time and information about this literature.

I have been talking for a long time now, but first I would like to start out by asking what everyone thinks about this initiative. We have a comment from Ms. Kawakami who could not be here today, so I would like to read it on her behalf.

"Tales of Ise is a collection of tales in the form of poems from the Heian Period. This work has been adored in Japan for a long time and I have heard that it was a long time best seller during the Edo Period. I wanted to make Tales of Ise that depicts human basics in a simple and powerful manner into a novel based on Ise. That being said, I cannot directly take Tales of Ise and make it into a novel. As an author, I still don’t know what story will be formed, but I hope Tales of Ise can provide some support for this story."

This is the comment from Hiromi Kawakami. To add to this, I would like to say that Ms. Kawakami has expressed agreement towards our spirit and intention. Ms. Kawakami will be releasing a new novel series from next year January in the New Year issue of Fujin Koron. We heard that she was going to do the series and wanted this project to be reflected on the series so NIJL has been packed with various workshops over the past two months. I hope you all can take a look at Hiromi Kawakami’s new novel starting from the New Year issue of Fujin Koron.

To continue, the guests I have introduced before, in fact, they have already started their work and visited the Institute a number of times since the summer. Everyone here came to NIJL one by one and physically turned the pages of transcribed books and ancient literature from 200 to 300 years ago going all the way back to the Kamakura period. What was your first impression when coming into contact with these and what did you feel was the allure of actual classic Japanese literature? We’ll start with Mr. Nagatsuka.

Nagatsuka:

I first visited the Institute in early September and was shown a number of books. As Mr. Campbell said before about the database, if we take a single pose as an example, an image of that pose can create an infinite amount of ideas, so I really wanted to be a part of this project with the extreme interest in how this database should be utilized.

When I actually went to the institute, a lot of people there were waiting to show me many different kinds of classic literature. I went to the institute with the idea of just having a talk without thinking too much into it, but I was able to encounter many books there. Of course, I listened to what everyone had to say and thought about how I can connect this to the theater, but the most significant part of my visit was being able to come into contact with the actual books. The connection between theater and classic literature is the moment the pages of the book is turned. The act of turning the pages itself, can be similar to experiencing some sort of drama that has passed through a certain time period. There are special aspects in how experts turn pages, or how there are different ways of opening and closing scrolls. For us performers, it involves using our physical bodies, so can stories be spun from our physical expressions? When investigating the process of making these books, is there something fused to the story lying dormant in the classic literature? This was how I was already thinking the moment of my encounter.

Campbell: Thank you very much. I remember when you first encountered a number of different bounded books and old books and you said that drama can be created from this encounter. That idea is out of the range of our thought, so it was very interesting. Yamamura, how about you?

Yamamura: I create animation and picture books and I’ve recently started collecting old picture books. I am especially fond of books before WWII. Books made before the photomechanical process include beautiful printing techniques such as lithography, copperplate engraving and wood block printing. I am very interested in these old books with pictures, so I was very much looking forward to experience these books first hand when hearing about the large number of old books with pictures at the National Institute of Japanese Language from Mr. Campbell. Current photography printing has a naturally high quality. However, in the case of lithography, the lithography artist directly carries out the lithography printing process and dozens of colors of ink can be used at once unlike the photomechanical process which uses only 4 colors. There are also copies with hand coloring and hand writing with all the pictures drawn to the actual size of the book. I try to communicate my ideas and feelings visually so looking at pictures which are hand written or directly pressed on a block for printing enables more of a sensation than pictures that are printed using one single base of information. I can experience something that happened 100 or 200 years ago as if it is happening right now. It is extremely interesting to hold information which was once really alive, in my own hands. I have made only two visits to NIJL so I would like experience a lot more different information.

Campbell: Thank you very much. Mr. Yamamura has a lot of different types of works and styles. For example, replacing the world of Kojiki into a short animation and creating completely new expressions. It is very exciting to see what kind of concepts are created by mixing borderless technology with an abundance of ideas.

Yamamura: In particular, I have recently been very interested in visual effects that combine text and pictures. Even in my own animation, I have started to intentionally include text without audio on the screen, so I feel that we can make some developments with this project.

Campbell:

Thank you very much.

Last year, Mr. MacMillan produced a wonderful translation of Tales of Ise which was highly acclaimed. Meanwhile, the world’s largest collection of documents relating to Tales of Ise with over 1,000 materials called the Tesshinsai Library was donated to NIJL last year and has been holding the special exhibition The Splendors of Tales of Ise at NIJL in Tachikawa since last week (Note: October 11th 2017 – December 16th 2017).

Tales of Ise has already been translated, in fact, many works were based on Ariwara no Narihira throughout the Kamakura Period and Muromachi Period, and Edo Period until days of Tokugawa shogunate. He has been reborn over and over, been embellished and different accounts have been added including parodies and erotic literature. The world of Japanese literature and aesthetics cannot be described without Tales of Ise and we have accumulated an extremely large amount of resources on this work. Mr. MacMillan had the chance to take a look at these. What did you feel about these and what are you searching for from these materials? Please give us your thoughts.

MacMillan:

It took about 5 years to translate Tales of Ise. However, I translated it from a printable type. I cannot read characters in running form, so I relied on the text provided by a large publishing company and translated the text while referring to the notation. Professor Tokuro Yamamoto instructed me in the process. He introduced me to the owner of the Tesshinsai Library Ashizawa and parts of illustrations from this collection are included in my version.

I was able to see this collection first hand along with other byobue pictures drawn on a folding screen and nehanzu pictures from Ariwara no Narihira which were impressive. As Ms. Kawakami’s message said earlier, Tales of Ise was a best seller in the Edo Period. It is a wonderful piece that has been newly published every year. However, it has almost been forgotten nowadays. Therefore, I am extremely appreciative of this exhibition and excited that everyone can get a chance to see this collection.

During the exhibition, I found out through notations on how Tales of Ise was conveyed and how a book known as Nise Monogatari was published, which made me even more excited. I also saw translations of Tales of Ise providing me with a lot of excitement.

Campbell:

Thank you very much. The Nise Monogatari you talked about came out in the 17th century and there were parodies and erotic versions such as the Koshoku Ise Monogatari and Tawareo Ise Monogatari, which are not very popular nowadays. It is almost impossible to order them off the Internet or find them immediately at the library. One of our objectives is for Mr. MacMillan to find wonderful gemstones and to bring them from Japan to English speaking regions to provide excitement to readers from other countries. It would be interesting if the opposite was done with works from English speaking regions.

Aside from that, it is important to know what current overseas readers are looking for. There are a lot of dormant works that have been adored by people of the time in addition to the works selected from the Meiji Period. I hope we can search through these works and find some good ones to make wonderful translations of.

Back to the National Institution of Japanese Language. Mr. Nagatsuka mentioned earlier, there are many people waiting there. I think there is a gap of the paths taken by artists and the translator, words used, and sceneries imagined by artists and the translator between the ideas and vocabulary used by researchers of Japanese classic literature. We don’t ask these people to just dive into this vast ocean of information by themselves. Someone to provide navigation is necessary. Therefore, the classics interpreter, Ms. Arisawa here with us today is an important presence.

Therefore, I would like to ask to everyone, what type of gaps were felt, what were you seeking for? When we stood alongside and navigating during production, what were some things you realized, things that were different and things you would like the research community to do? Please give us your thoughts. Anyone can start.

Nagatsuka: I’m not really sure yet, but I’ve been to the institute about 3 times. Whenever I go, the professors greet me, and they show me piece after piece of classic literature. Each time I go, I stay for around 3 hours, a really intensive 3 hours in which I learn so much it makes my head spin. It is extremely fun. In the Tales of Genji Series, we looked at so many different versions of, I lost count.

Campbell: On that day we looked at around 30 versions. Tales of Genji started in the Kamakura Period and we brought out all the different versions until the beginning of the Meiji Period including annotations.

Nagatsuka: And that was just part of the experience. In such a short time, I wondered how much explanation there was. The professors just really wanted to talk about Tales of Genji.

Campbell: That cannot be helped (laughs).

Nagatsuka:

I was very surprised by this. I am constantly thinking about how to relate classic literature to theater. Having met with a lot of different professors, I thought about doing plays with these professors as a Bunshigeki (amateur theater written and acted by the writers). That’s a joke, but that is how much of a strong impression they have left on me.

When I talked about how I am currently interested in the books, the professors will talk about the unique characteristics the book possess. What I felt was most heartening was when the interest in wanting to delve a little further into the literature is clear, the professors would provide me with knowledge which would excite me even more. That was interesting.

At the same time, I wondered how to connect the areas which cannot be expressed with words. In order to delve deeper, language for delving deeper may become necessary. I have absolutely no knowledge of classic literature, so when the professors provide a deeper understanding and connection of the words I don’t know, when I communicate what I felt in my acting brain, the part of my brain didn’t have any knowledge about classic literature, maybe like Ms. Arisawa, who can insert the meanings so I can delve deeper enabling me to go on an amazing journey.

Campbell:

Thank you very much. That was an insightful request, we take this as a challenge. This is exactly right. In the modern age of the past 150 years, classic literature studies and Japanese history researchers have had their own individual methods and procedures establishing their fields while gradually sharing the paradigm. When researchers provide information to society as a whole, they naturally speak in their own system of logic and words. Their information is correct, but there are many cases where this information is not conveyed. The objective of this Initiative is to take a few steps away from this system of logic and journey together with those from other fields through the world of classic literature. Although this is the basis of Japanese culture, before there were characters written in running form, ancient texts and Chinese classics written in many different styles making the door to this world difficult to open. We are not only considering how to carefully open this "door" and how to read these texts, but we are also taking chances at how to promote new creation from this.

Therefore, when Mr. Nagatsuka talked about the desire of "wanting to delve in further," it may seem exaggerated, but this is a major challenge for Japanese literary scholars. I call it a challenge, but it is something we must consider and take action.

Likewise, the classics interpreter who we talked about before and is part of this Initiative at NIJL is expected to show the people close to the forest we live in, especially the creators and translators how to carry over not only the base meaning of the texts, but also the subtle nuances. They may be considered as "drawing bridges over moats." There are scientific and technical interpreters for science fields which require a high level of skill. However, in the current situation, this has not been developed in the research community of basic literature when sharing information with the media, converting it to ICT or translating it into other languages. Therefore, we are training classics interpreters with these job skills in preparation for work in the real world.

The first of these interpreters is sitting right next to me, Ms. Arisawa. From listening to all of this, is there anything you want to ask, your aspirations or something you would like to do?

Arisawa:

We heard about workshops starting earlier. It is very interesting to see where people look and what people are interested in when looking at old books. Time spent talking while looking at things is stimulating. I have investigated, analyzed and given presentations on fields of my expertise to the academic world before, but this project plays the role of creating something new from classic literature so I strongly feel I need to incorporate different perspectives than what I used to have.

I would like to relate these ideas, and this may be a little vague, but I would like to hear from artists and creators about what they felt and thought about the writers and creators of classic literature and books when they read these works.

Yamamura:

I have high expectations for the role of the classics interpreter. For someone like me who is unfamiliar with classic literature, not only can I not read the kanji characters, but characters in running form as well. The words used are also, of course, different and I keenly feel the necessity of translation of the actual meaning to firmly understand the text.

There are several experts in each field at the NIJL. To go back to the previous question, when I first visited the Institute, it wasn’t the movie Seven Samurais but left a similar impression of a bunch of different skilled experts standing after another. When I create, I am naturally attracted to the past and I may not be able to find the actual origin. However, as my interest deepens and finding out where the origin is, I had no choice but to become familiar with the classic books.

In reality, I didn’t really like classic literature since I was in high school. I wasn’t interested in it. When young, it’s natural to be attracted more towards modern things but as I get older, I am becoming more and more interested in older things. However, even Japanese people need a Japanese translation in this situation. In order to learn the meanings, I think that if the meaning does not revive in present times in an active form, the meaning cannot be understood. There may be something helpful that we can do. We can translate and interpret the creators who are not alive today. It is as if we are talking with these creators of the past, so I hope we can find something interesting.

Campbell:

Thank you very much. As Mr. Yamamura just said, a distinctive feature of Japanese text is the need to start from the character itself, in other words, orthography. To put it simply, when looking at languages of the world, the fact that Japanese has continued to maintain its characters for over 1,000 years with events and concepts being written autonomously using these characters and the meanings being conveyed until now through classic literature, is close to a miracle. Characters were significantly revised from the 1870s and the language as a whole was also significantly revised from the 1890s establishing standards in spoken language based on printed text. However, these standards created a discontinuance in between the literary world up until then. Speaking of inheritance and discontinuation, it is also a modern process itself, but not being able to access conventional Japanese passed down is a significant loss. The uncommon state of not being able to reach out to another generation is a point which requires attention when looking at Japan.

It is important to consider how the feelings, prayers and wars, love, various daily emotions were rooted on the people’s lives. There are stunningly beautiful visual works of art and wonderful architecture as well as performing arts which are magnificent cultural assets reflecting the towns which supported people’s lifestyles as well as the spirt of the people. But I feel that literary works written as testimonies for that people lived is the most direct form of art which seems to show the appeal of human life in a detailed and three-dimensional manner.

When discussing to start this Initiative, we decided to not start with nothing, but to use materials which were on hand as much as possible. This may be a bit off topic, but this is the first time showing the logo of the NIJL Arts Initiative. The English version is at the Institute but this one was created by the talented graphic designer Hironori Sugie at Cryptomeria.

The design above is the forest of classic literature as mentioned earlier. The three pillars stand for the creators, the research community and the interpreters in the middle. All of the pillars are connected with their own colors. These three parts are combined to signify the aim to create new culture.

The text of the logo is an original font. The first version was incredibly gorgeous and the text was beautiful, but it was missing something. I apologize to Mr. Sugie who is not here today for not being able to give a sufficient enough description.

There is a lot of valuable literature at the National Institute for Japanese Literature. Among these Koshoku Ichidai Otoko written by Saikaku Ihara is possibly the first edition printing and this printed book from 1682 has incredible breath-taking characters. Individual characters were selected from the text in a process called shuji and each were traced. These were then brought closer to the modern-day hiragana and kanji forms. In other words, the cultural genes of a merchant who lived in Osaka in the 17th century was revived into this new expression.

I would like to give a description of the name of the Initiative. The English acronym for the National Institute of Japanese Literature is NIJL which is pronounced "Nigel." This sounds like an old-time actor from England, but it is easy to remember so we called this the NIJL Arts Initiative in English. In this way, we aim to utilize different types of cultures, especially literary materials that have been unutilized to create new things and events which did not exist yesterday. A few days ago, the Mitsukoshi Nihonbashi main location and Ginza location each collaborated with NIJL to put on the Edo Cooking Fair on the floor which has their food corners. The NIJL Arts Initiative has expectations for and is putting most of its efforts towards art expression. There must be knowledge, information and sensibility which are all important for humans, among the classic literature books or images at our Institute which no one may have been exposed to since modern times over the past 200-300 years. I believe this is a massive treasure for sharing art and different cultures.

It is almost time to finish. I hope you were able to see the shape, outline of the Initiative, what kind of things are required for us. I would like everyone to give a brief message

Nagatsuka:

I am in the theater, so I have to incorporate this in my body somehow. It is extremely important for me to experience this for myself. It is very important for me to go to the Institute a few times a month and get various different types of information. Thinking that this is the way, for example there is a physicality in the books as they are actually copied by people.

As a trousseau of Japanese literature, Tales of Genji was written by a courtier not in the samurai society which is interesting and a good story. In short, on top of the fun of looking for the roots of one book, the transcription of the book is also interesting. Also hearing about when printed books were created and when printing of text started is mysterious and it was exciting to find out about how many people were involved in the process. Our discussions on printed books were really interesting. Transcribing books was a painstaking process and printing books involved having to carve the extravagant characters in running form. Kana text is printed in moveable type but characters in running form combine two characters into one, so I felt this is a very difficult task.

I wonder how many people were involved in the process. I wonder where to explore in order to meet these people or even if it is possible. This cannot be done with just my idea alone, even if it is transcribed, how much of it has been passed down from the writer, or how dramatically has it changed depending on the transcription process? This also includes stories that do not exist anymore. The theater is also an art of time so that time comes out of a book and I think of whether I can create something which I can travel to from the book currently in front of me. Firstly, I would like to see how far one book can go. It would be interesting to check several books and advance the stories.

Campbell: What do you think Mr. Yamamura?

Yamamura:

It’s still a little vague for me, but during my two visits I was able to talk with others and I had interest for the relationship between characters and pictures, so I talked about being interested in the history of speech bubbles. There were no specific speech bubbles but when I was shown the images of the Kibyōshi, I asked if these were speech bubbles and was told that this was an expression of someone’s dream. A diagonal line leads out from a character and a visual is inserted here. This left an impression with me and I thought about how expressions have transitioned for dreams of Japanese people. As one of the things I want among Japanese classic literature is that I think there are distinctive qualities of Japanese people such as their spirit, thought process and how they hold identities.

Japanese poetry such as Man'yōshū includes a lot of poems about dreams. For example, there is a sense in Japan that dreams are not subjectively seen by individuals but are the thoughts of others, so dreams are connected with a shared suppressed unconsciousness like when others appear in your dream. In order to understand the deep Japanese spirit, you may be able to find out something interesting by searching through dreams. In Konjaku Monogatari, the wife and husband see the same dream at the same time in different places. This type of synchronicity may seem mysterious. I would like to search for these types of phenomena actually happening in Japan. I myself, think that the expression of animation is similar to a dream, shaping inner visuals can enable deep sharing with others. I think about if there is such a thing, and that if expressing it as a reality is possible.

With classic literature, a bundle of paper is like animation. I draw all animation on paper which is very similar to the feeling of taking an actual book in your hands. For example, one cut of an animation is drawn as a bundle of 100 sheets of paper. The flow of time, atmosphere and world are created. In the case of books, there is a world and atmosphere inside the closed book cover which can be seen as soon as you open it. The time axis and re-creation methods differ but I feel animation is really similar to books. I heard that dreams are actually a very new and popular topic in research of text and there are people already carrying out research on this, so I think it would be a good idea to first understand the preceding research in our own special way and then discover new things and ourselves.

MacMillan:

I am very thankful for this program and I expect great things out of it. The National Institute for Japanese Literature is an inexhaustible treasure trove and I always discover something new every time I visit. I would like to have the opportunity to further translate more materials related to Tales of Ise. However, I was consulted about a project earlier and I am creating the world’s first English karuta cards One Hundred Poets, One Poem Each. However, this time I took designers to Prof. Koyama, wanting to design after viewing items such as past karuta cards designs. This is because young designers can create incredibly wonderful designs these days, but they lack knowledge of classic literature. For example, they don’t fully grasp the concepts of seasonal feeling or the beauty of the four seasons in One Hundred Poets, One Poem Each so they may not be able to come up with ideas. Therefore, I am expecting the Institute to play a big role.

Many people tend to think that the world of classic literature is completely different and far from the modern world which is the loneliest way of look at it for me as a translator of Japanese classic literature. People see translation of modern novelists such as Haruki Murakami and translation of classic literature as completely different. However, for me, classic literature is literature where the ancestors of Japanese people have passed down to them, so it is not separate from modern times. The more excavated it is, new forms cannot be created in modern society. I hope and have great expectations that this program can make such significant strides.

Campbell: Thank you very much. There are so many things to talk about and I would like to continue but we are out of time. Thank you all for coming today.